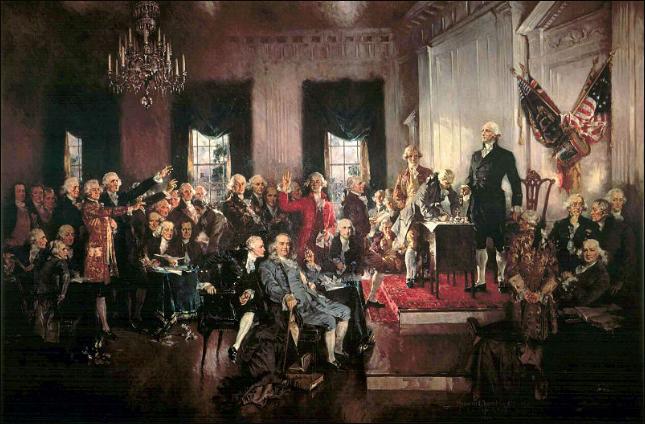

On May 25, 1787, delegates

representing every state except Rhode Island convened at Philadelphia's

Pennsylvania State House for the Constitutional Convention. The

building, which is now known as Independence Hall, had earlier seen the

drafting of the Declaration of Independence and the signing of the

Articles of Confederation. The assembly immediately discarded the idea

of amending the Articles of Confederation and set about drawing up a new

scheme of government. Revolutionary War hero George Washington, a

delegate from Virginia, was elected convention president. The delegates

were generally convinced that an effective central government with a

wide range of enforceable powers must replace the weaker Congress

established by the Articles of Confederation. The high intellectual

quality of the delegates to the convention was remarkable.

During an intensive debate, the delegates devised a brilliant federal

organization characterized by an intricate system of checks and

balances. The convention was divided over the issue of state

representation in Congress, as more-populated states sought proportional

legislation, and smaller states wanted equal representation. The problem

was resolved by the Connecticut Compromise, which proposed a bicameral

legislature with proportional representation in the lower house (House

of Representatives) and equal representation of the states in the upper

house (Senate).

During our 2013 small monthly group studying the

debates (during the Constitutional Convention) I was especially

impressed with what Benjamin Franklin said on June 2, 1787 as the

Convention further considered the power of the Executive department. He

spoke about a "favorite idea of his: that officers of government

should not receive salaries." Franklin obviously knew history and

human nature, so he had to speak up. What he said was prophetic:

"It is with reluctance that I rise to express a

disapprobation of any one article of the plan for which we are so much

obliged to the honorable gentleman who laid it before us. From its first

reading I have born a good will to it, and in general wished it success.

In this particular of salaries to the Executive branch I happen to

differ; and as my opinion may appear new and chimerical, it is only from

a persuasion that it is right, and from a sense of duty that I hazard

it. The Committee will judge of my reasons when they have heard them.,

and their judgment may possibly change mine...I think I see

inconveniences in the appoinment of salaries; I see none in refusing

them, but on the contrary, great advantages.

"Sir, there are two passions which have a

powerful influence on the affairs of men. These are ambition and

avarice; the love of power, and the love of money. Separately each of

these has great force in prompting men to action; but when united in

view of the same object, they have in many minds the most violent

effects. Place before the eyes of such men, a post of honour that shall

be at the same time a place of profit, and they will move heaven and

earth to obtain it. The vast number of such places it is that renders

the British Government so tempestuous. The struggles for them are the

true sources of all those factions which are perpetually dividing the

Nation, distracting its Councils, hurrying sometimes into fruitless and

mischievous wars, and often compelling a submission to dishonorable

terms of peace.

"And of what kind are the men that will strive

for this profitable pre-eminence, through all the bustle of cabal, the

heat of contention, the infinite mutual abuse of parties, tearing to

pieces the best of characters? It will not be the wise and moderate; the

lovers of peace and good order, the men fittest for the trust. It will

be the bold and the violent, the men of strong passions and

indefatigable activity in their selfish pursuits. These will thrust

themselves into your Government and be your rulers...And these too will

be mistaken in the expected happiness of their situation: For their

vanquished competitors of the same spirit, and from the same motives

will perpetually be endeavouring to distress their administration,

thwart their measures, and render them odious to the people.

"Besides these evils, Sir, though we may set

out in the beginning with moderate salaries, we shall find that such

will not be of long continuance. Reasons will never be wanting for

proposed augmentations. And there will always be a party for giving more

to the rulers, that the rulers may be able in return to give more to

them....Hence as all history informs us, there has been in every State

and Kingdom a constant kind of warfare between the governing and

governed: the one striving to obtain more for its support, and the other

to pay less. And this has alone occasioned great convulsions, actual

civil wars, ending either in dethroning of the Princes, or enslaving of

the people. Generally indeed the ruling power carries its point, the

revenues of princes constantly increasing, and we see that they are

never satisfied, but always in want of more. The more the people are

discontented with the oppression of taxes; the greater need the prince

has of money to distribute among his partizans and pay the troops that

are to suppress all resistance, and enable him to plunder at pleasure.

There is scarce a king in a hundred who would not, if he could, follow

the example of Pharoah, get first all the people's money, then all their

lands, and then make them and their children servants forever. It will

be said, that we don't propose to establish Kings. I know it. But there

is a natural inclination in mankind to Kingly Government. It sometimes

relieves them from Aristocratic domination. They had rather have one

tyrant than five hundred. It gives more of the appearance of equality

among Citizens, and that they like. I am apprehensive therefore, perhaps

too apprehensive, that the Government of these States, may in future

times, end in a Monarchy. But this Catastrophe I think may be long

delayed, if in our proposed System we do not sow the seeds of

contention, action and tumult, by making our posts of honor, places of

profit. If we do, I fear that though we do employ at first a number, and

not a single person, the number will in time be set aside, it will only

nourish the fetus of a King, as the honorable gentleman from Virginia

very aptly expressed it, and a King will the sooner be set over us.

"It may be imagined by some that this is an

Utopian Idea, and that we can never find men to serve us in the

Executive department, without paying them well for their services. I

conceive this to be a mistake. Some existing facts present themselves to

me, which incline me to a contrary opinion. The high Sheriff of a County

in England is an honorable office, but it is not a profitable one. It is

rather expensive and therefore not sought for. But yet it is executed,

and usually by some of the principal Gentlemen of the County. In France,

the office of Counselor or Member of their Judiciary Parliaments is more

honorable. It is therefore purchased at a high price: There are indeed

fees on the law proceedings, which are divided among them, but these

fees do not amount to more than three percent on the sum paid for the

place. Therefore as legal interest is there at five percent they in fact

pay two percent for being allowed to do the Judiciary business of the

Nation, which is at the same time entirely exempt from the burden of

paying them any salaries for their services. I do not however mean to

recommend this as an eligible mode for our Judiciary department. I only

bring the instance to show that the pleasure of doing good and serving

their Country and the respect of such conduct entitles them to, are

sufficient motives with some minds to give up a great portion of their

time to the public, without the mean inducement of pecuniary

satisfaction.

"Another instance is that of a respectable

Society who have made the experiment, and practiced it with success more

than an hundred years. I mean the Quakers. It is an established rule

with them, that they are not to go to law; but in their controversies

they must apply to their monthly, quarterly and yearly meetings.

Committees of these sit with patience to hear the parties, and spend

much time in composing their differences. In doing this, they are

supported by a sense of duty, and the respect paid to usefulness. It is

honorable to be so employed, but it was never made profitable by

salaries, fees, or perquisites. And indeed in all cases of public

service the less the profit the greater the honor.

"To bring the matter nearer home, have we not

seen, the great and most important of our offices, that of General of

our armies executed for eight years together without the smallest

salary, by a Patriot whom I will not now offend by any other praise; and

this through fatigues and distresses in common with the other brave men

his military friends and companions, and the constant anxieties peculiar

to his station? And shall we doubt finding three or four men in all the

United States, with public spirit enough to bear sitting in peaceful

Council for perhaps an equal term, merely to preside over our civil

concerns, and see that our laws are duly executed? Sir, I have a better

opinion of our Country. I think we shall never be without a sufficient

number of wise and good men to undertake and execute well and faithfully

the office in question.

"Sir, the saving of the salaries that may at

first be proposed is not an object with me. The subsequent mischief's of

proposing them are what I apprehend. And therefore it is, that I move

the amendment. If it is not seconded or accepted I must be contented

with the satisfaction of having delivered my opinion frankly and done my

duty."

The motion was seconded by Colonel Hamilton with

the view he said merely of bringing so respectable a proposition before

the Committee, and which was besides enforced by arguments that had a

certain degree of weight. No debate ensued, and the proposition was

postponed for the consideration of the members. It was treated with

great respect, but rather for the author of it, than from any apparent

conviction of its expediency or practicability.

During an intensive debate, the delegates devised

a brilliant federal organization characterized by an intricate system of

checks and balances. The convention was divided over the issue of state

representation in Congress, as more-populated states sought proportional

legislation, and smaller states wanted equal representation. The problem

was resolved by the Connecticut Compromise, which proposed a bicameral

legislature with proportional representation in the lower house (House

of Representatives) and equal representation of the states in the upper

house (Senate).

On September 17, 1787, the Constitution of the

United States of America is signed by 38 of 41 delegates present at the

conclusion of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. As dictated

by Article VII, the document would not become binding until it was

ratified by nine of the 13 states. Beginning on December 7, five

states--Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and

Connecticut--ratified it in quick succession. However, other states,

especially Massachusetts, opposed the document, as it failed to reserve

undelegated powers to the states and lacked constitutional protection of

basic political rights, such as freedom of speech, religion, and the

press. In February 1788, a compromise was reached under which

Massachusetts and other states would agree to ratify the document with

the assurance that amendments would be immediately proposed. The

Constitution was thus narrowly ratified in Massachusetts, followed by

Maryland and South Carolina. On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the

ninth state to ratify the document, and it was subsequently agreed that

government under the U.S. Constitution would begin on March 4, 1789. In

June, Virginia ratified the Constitution, followed by New York in July.

On September 25, 1789, the first Congress of the United States adopted

12 amendments to the U.S. Constitution--the Bill of Rights--and sent

them to the states for ratification. Ten of these amendments were

ratified in 1791. In November 1789, North Carolina became the 12th state

to ratify the U.S. Constitution. Rhode Island, which opposed federal

control of currency and was critical of compromise on the issue of

slavery, resisted ratifying the Constitution until the U.S. government

threatened to sever commercial relations with the state. On May 29,

1790, Rhode Island voted by two votes to ratify the document, and the

last of the original 13 colonies joined the United States. Today, the

U.S. Constitution is the oldest written constitution in operation in the

world.

Back