New

Mexico is a complex mural with mountains and desert that

dominant the landscape. There are approximately

seventy-three ranges, from Animas to Zuni. They include

seven peaks rising above 13,000 feet, eighty-five more than

two miles high, and more than three hundred notable enough

to warrant names. They're all part of the Southern Rockies,

and abound with strange legends and myths. Aside from UFO's,

the treasure of Victorio Peak is probably the most

notorious. The peak's a

craggy outcropping of

rock barely five hundred feet tall located in the center of

a dry desert lake known as the Hembrillo Basin. Beyond

the Basin is a hundred mile area of desert known as the

Jornada del Muerto, that means Journey of Death,

because during the early Spanish explorations, travelers

took this shortcut through hostile Apache Indian territory.

Many died from Indian attacks, and others from the terrible

desert. Victorio Peak lies within the White Sands Missile

Range in south central New Mexico. Many years ago I saw the

intriguing story about the Peak's hidden treasure on the

television Unsolved Mystery series. Here's

60 Minutes with Dan Rather.

I'd forgotten about it until visiting with friends in

Texas.

Floyd and his friend Pat were getting ready to

look for treasure in an area where Pat found

found three old metal bars in a cave on the old

Spanish trail in New Mexico. They bore the Spanish stamp. He

was overcome with joy that they might be gold. He gave them

to an expert to examine and was told that they were Spanish

brass used for the bells in the missions. Pat was

disappointed. Later he tried to find the bars, but couldn't

locate them. Then he got a call from some explorers who

wanted him to go treasure hunting with them, because they

heard he'd found three gold bars. Later I did some research

and discovered that the Spanish gold bars contained a large

percentage of copper.

It reminded me of the intrigue surrounding the Victoria Peak

mystery.

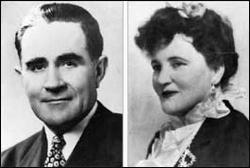

Long

before Victoria Peak was taken over and surrounded by the

government, a man named Milton Ernest (Doc) Noss took time

exploring Victorio Peak while he was deer hunting. Noss was

born in Oklahoma, but traveled all over the Southwest

seeking adventure. In 1933, he married Ova (Babe)

Beckworth. They made their home in Hot Springs, New Mexico,

which was later became known as Truth or Consequences,

after the popular television game show of the 1950's.

November 1937, Doc, Babe, and four others left on a deer

hunt into the Hembrillo Basin. Setting up camp on the desert

floor at the base of Victorio Peak, the men headed into the

wilderness, while their wives stayed at camp. Hunting

by himself, Doc scouted the base of the mountain. When

it began to rain, Doc sought shelter under a rocky overhang

near the summit of the mountain. While waiting for the

rain to subside he noticed a stone that looked as if it had

been “worked” in some fashion. Reaching down, he was

unable to budge it, but after digging around the rock, he

got his hands under it. Lifting the rock, he found a

hole that lead straight down into the mountain.

Peering into the darkness, Doc saw an old man-made shaft

with a thick, wooden pole attached at one side. Doc thought

that he had discovered an old abandoned mineshaft.

When the rain finally stopped, Doc returned to camp, telling

Babe of the discovery. The two decided to keep the

discovery between themselves and return to the inspect the

shaft later.

Within

just a few days, Doc and Babe were back at the site with

ropes and flashlights. Testing the old wooden pole attached

to one side of the passage, Doc rejected the idea of using

it dropped into the shaft with a rope instead. While

Babe looked on from above, Doc inched his way down the

narrow passageway into the mountain nearly sixty feet.

Near the bottom, he encountered a huge boulder hanging from

the ceiling, almost blocking his way.

Finally reaching the bottom, Doc stepped into a chamber the

size of a small room. On the walls were drawings ,

some painted and others chiseled, that appeared to have been

made by Indians. At one end of the chamber, the shaft

continued downward. Once again, Doc began to descend,

this time about 125 feet before the shaft again leveled off

into a large natural cavern. Several smaller rooms had

been chiseled from the rock along one wall. Stepping

into the eerie darkness, Doc was alarmed when he saw a human

skeleton, kneeling and securely tied to a stake driven into

the ground. The skeleton’s hands were bound behind its

back -- apparently, the person had been deliberately left

there to die. Within moments he found more skeletons,

most of them bound and secured to stakes like the first.

Exploring further he found yet even more skeletons stacked

in a small enclosure, much like a burial chamber. All told,

he reportedly found twenty-seven human skeletons in the

caverns of the mountain.

As Doc continued to explore the

side caverns, he found a hoard of treasure including coins,

jewels, saddles and priceless artifacts including a gold

statue of the Virgin Mary. He also found some old letters,

the most recent of which was dated 1880. This treasure was

only the beginning. In a deeper cavern, Doc found what he

thought was a stack of worthless iron bars. He estimated

there were thousands of these bars, each weighing over forty

pounds stacked against a wall. He was barely able to lift

one, mush less think of carrying it back to the surface.

Later, the wealth in the cave would be calculated to be

worth more than two billion dollars. Doc filled his pockets

with gold coins, grabbed a couple of jeweled swords, and

laboriously returned to Babe waiting anxiously at the

surface. After telling her about what he'd seen and showing

her the loot, she insisted he go back into the mine for one

of the iron bars. After much searching, he found a small

iron bar that he could carry back through the narrow

passageway. When he reached the surface, he told Babe, "This

is the last one of them babies I'm gonna bring out." Babe

rolled the bar over and noticed a yellow gleam where the

gravel of the hillside had scratched off centuries of black

grime. What looked like a piece of iron was actually a solid

gold bar.

After the discovery of the

treasure, Doc and Babe spent every free moment exploring the

tunnels inside the peak, living in a tent at the base of it.

On each trip, Doc would retrieve two gold bars and as many

artifacts as he could carry. At one time, he brought out a

crown, which contained two hundred forty-three diamonds and

one pigeon-blood ruby. Yet, Doc trusted no one, not even

Babe, disappearing into the desert, hiding pieces of the

treasure in places that he never revealed.

Among the artifacts, Doc is

reported to have retrieved were documents dated 1797, which

he buried in the desert in a Wells Fargo chest along with

various other treasures. Although the originals have never

been recovered, a copy of one of the documents was a

translation from Pope Pius III:

"Seven

is the holy number," the passage begins. It then

continues for several lines before ending with a cryptic

message: "In seven languages, seven signs, and languages

in seven foreign nations, look for the Seven Cities of Gold.

Seventy miles north of El Paso del Norte in the seventh

peak, Soledad, these cities have seven sealed doors, three

sealed toward the rising of the Sol sun, three sealed toward

the setting of the Sol sun, one deep within Casa del Cueva

de Oro, at high noon. Receive health, wealth, and honor.

"Seven

is the holy number," the passage begins. It then

continues for several lines before ending with a cryptic

message: "In seven languages, seven signs, and languages

in seven foreign nations, look for the Seven Cities of Gold.

Seventy miles north of El Paso del Norte in the seventh

peak, Soledad, these cities have seven sealed doors, three

sealed toward the rising of the Sol sun, three sealed toward

the setting of the Sol sun, one deep within Casa del Cueva

de Oro, at high noon. Receive health, wealth, and honor.

Believers think that Doc Noss

found the Casa del Cueva de Oro, Spanish for the House of

the Golden Cave. "Soledad" was the former name of

Victorio Peak, and Doc apparently found the seventh door

located at high noon, but the promised health,

wealth, and honor would evade him. Four years before his

discovery, Congress had passed the Gold Act, which outlawed

the private ownership of gold, so Doc would be unable to

profit from his treasure on the open market. He didn't care

about the historical value of the treasure's inside Victorio

Peak, so he mostly ignored the pouches, packs and artifacts,

while he concentrated on the gold coins and bars. Although

he was unable to sell the gold bars on the open market, Noss

continued to work steadily to remove the treasure.

In the spring of 1938, Doc Noss

and Babe went to Santa Fe to establish legal ownership of

the find, filing a lease with the State of New Mexico for

the entire section of land surrounding Victorio Peak.

Subsequently, he also filed several mining claims on and

around Victorio Peak, as well as a treasure trove claim.

With legal ownership established, Noss began to openly work

the claim, but he also became increasingly paranoid, hiding

the gold bars all over the desert.

When

Doc’s story eventually hit the headlines, scholars began

speculating on how the enormous treasure could have come to

be stashed inside Victorio Peak. Some believe that Doc

Noss found the Casa del Cueva de Oro. Others believe that

Noss found the treasure of Don Juan de Onate, who, in 1598,

founded New Mexico as a Spanish colony.

Seeking

out the Seven Cities of Gold, Onate was said to have been a

cruel man, brutally subjugating the Indians to do his

bidding by beating and torturing them. Reportedly, he

amassed a fortune of gold, silver treasure and jewels

before being ordered back to Mexico City in 1607.

Seeking

out the Seven Cities of Gold, Onate was said to have been a

cruel man, brutally subjugating the Indians to do his

bidding by beating and torturing them. Reportedly, he

amassed a fortune of gold, silver treasure and jewels

before being ordered back to Mexico City in 1607.

Others speculate that

the treasure could be the missing wealth of Emperor

Maxmillian, who served as Mexico’s emperor in the

1860’s. When Maxmillian heard of plot to assassinate

him, he began to move his gold and treasures out of

Mexico. Legend says he sent a palace full of valuables

to the United States to be hidden. Maxmillian was

assassinated in 1867.

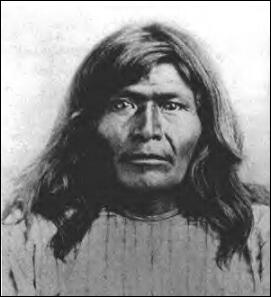

And then

Chief Victorio enters into the story? The most colorful

legend associated with the Victorio Peak treasure

concerns the great Warm Springs Apache war chief, who

used the entire Hembrillo Basin as his stronghold. He

absolutely refused to live on the San Carlos Reservation

in Arizona where his people died from hunger and insect

bites. Victorio’s land had always been in the mountains

of New Mexico, and a treaty between the Federal

government in Washington and his band had promised they

could stay on those lands as long as the "mountains

stand and the rivers flowed." With the discovery of gold

in the mountains, such did not happen, and in 1878, the

treaty was broken. Victorio went on the war path.

Knowing

how much the white man valued gold and having little use

for it himself, he amassed huge amounts of the yellow

mineral any way he could get it. He and his warriors

raided throughout the Jornada and the Rio Grande Valley,

attacking wagon trains, churches, immigrants, mail

coaches, and anything else that promised riches. He

raided the stage lines all over southern New Mexico and

Texas in an all-out war against the U. S. Army and the

Texas Rangers. He also took prisoners back to the Basin

and subjected them to elaborate torture as a test of

their bravery before killing them.

This could possibly

explain the skeletons in the cavern. It would also

explain the presence of the Wells Fargo bags,

packsaddles, letters and other artifacts dating to

Victorio’s time.

Another theory

is that the treasure belonged to a Catholic missionary named

Felipe La Rue, or La Ruz, as church documents are said to

give his name. He was a native of France and was among the

small group of priests who volunteered for service in

Mexico. His party sailed to Florida, crossed the Gulf of

Mexico to Vera Cruz, and from there, it went to Mexico City

by ox cart. After a short rest, Padre La Rue left for the

north, where he took up his work among the Indians and peons

at a large hacienda near what is now the city of Chihuahua,

reaching there in 1798. From the people at his new station,

he heard stories about a fabulous source of rich minerals in

the mountains to the north. If he was interested in these

stories, he did not reveal it. Instead, he continued with

his teachings and ministering to the sick and spiritual

needs of his small parish. Among his parishioners was an old

man, who had been an explorer and soldier of fortune during

his youth. This man had traveled widely over the country to

the north, and as Padre La Rue personally cared for this

ailing old man, the two became good friends.

One day, Padre

La Rue asked about the riches which lay to the north. The

old man said that if the good priest wanted gold, there was

a rich deposit of it located high in the mountains about two

days’ travel north of El Paso del Norte, which is the

present-day site of El Paso, Texas. According to the legend,

the man said, "After one day’s travel from El Paso del

Norte, you will come to three small peaks yet further to the

north. Upon first sight of these peaks, turn to the east and

cross the desert toward the mountains. In the mountains, you

will find a basin where there is a spring at the foot of a

solitary peak. On this peak, you will find gold." A few days

later, the old man died. It was not until the crops failed

that Padre La Rue thought of the solitary peak filled with

gold. His little parish needed water and a better climate,

and he called everyone together, asking if they would follow

him north. They all agreed, and the little party set out for

their new country. After crossing El Paso del Norte, they

followed the course of the Rio Grande to the small village

of La Mesilla near Las Cruces. North of there, they sighted

the three peaks and turned east across the dreaded Jornada

del Muerto, finally arriving in the San Andreas Mountains.

After a couple of days of exploration, they located a basin

in which there was a spring at the base of a solitary peak,

just as the old man had said. Scholars all believe this

basin was the Hembrillo Basin, and the solitary peak was

Soledad Peak. After a fierce battle between the Army and

Chief Victorio of the Apaches in 1880, the peak assumed a

new name of Victorio Peak. It is not to be confused with

Victoria Peak in the Black Range Mountains near Kingston,

New Mexico.

Padre La

Rue established a crude camp and sent the men out to

search for the gold the old man had promised was there.

On one side of the peak, they located a rich vein,

ultimately working the mine for years. They tunneled

into the mountain and followed the vein downward. The

deeper they went, the richer the ore became. The little

priest assigned dozens of monks and Indians to mine the

gold, form it into ingots and, except for whatever was

needed for supplies, stack it along one wall of a

natural cavern inside the mountain. Word eventually

reached church officials in Mexico City that the

hacienda had been abandoned, and Padre La Rue’s tiny

colony was missing. A search party went to investigate.

When they returned and reported that the entire

population had left for the mountains to the north,

soldiers were dispatched with orders to locate the

priest and demand an explanation. It was when a small

group was in La Mesilla purchasing supplies that they

learned the Mexican Army was on the horizon. Hurrying to

camp, they spread the alarm. It was one thing for Padre

La Rue to leave his post without permission of church

officials in Mexico City, but it was quite another not

to deliver the Royal Fifth (or Quinta) of the gold for

shipment to Spain. Padre La Rue was in a lot of trouble.

Padre La Rue immediately set about concealing all traces

of the mine. Working day and night, knowing the soldiers

were drawing ever closer, he had his little group labor

to conceal the entrance. When the soldiers finally

arrived and demanded to know where the gold came from

which was used to purchase the supplies in La Mesilla,

Padre La Rue refused to answer. He died under torture,

as did many of his followers, and although the soldiers

looked all over for evidence of a mine, they were forced

to return to Mexico City with nothing to show for their

long journey. The Lost Padre Mine, as it has been called

ever since, went into the history pages as a beloved

legend.

Meanwhile...In the Fall of 1939,

Doc wanted to enlarge the passageway into Victorio Peak so

that the treasures could be more easily removed.

Hiring a mining engineer by the name of S.E. Montgomery, the

two went into the mountain to blast out the shaft.

The engineer suggested eight sticks of dynamite, to which

Noss heatedly disagreed, claiming the mountain was too

unstable. The “expert” won the argument.

However, the blast was a disaster, causing a cave-in,

collapsing the fragile shafts, and effectively shutting Doc

out of his own mine. Doc tried several times to regain entry

into his mine, but the shaft was sealed with tons of debris.

All attempts failed, leaving him an embittered and angry

man, which caused problems in his marriage. Noss soon

deserted Babe and in November 1945, a divorce was granted.

Two years later, he married Violet Lena Boles, which would

further complicate ownership of the treasure rights for

years to come.

Now,

instead of having thousands of gold bars to draw from, Noss

had only a few hundred that he had hidden in the desert.

Becoming desperate for cash, Doc along with another man

allegedly transported gold bars, coins, jewels, and

artifacts into Arizona, selling them on the black market.

For nine years, Doc attempted to sell his gold, but it

was difficult finding buyers.

In 1948, Doc met

Charles Ryan, a Texan involved in drilling operations and

oil exploration in West Texas. Noss made an agreement

with Ryan to exchange some of the gold bars for $25,000 to

reopen the shaft. Meanwhile, Babe Noss had filed a

counter-claim on the entire area. Denied entry by the courts

until legalities could determine the legal owner of the

mine, Doc feared Ryan would back out of the deal. Sensing a

double-cross by Ryan, Doc dug up the gold that was to be

used in the exchange and reburied it in place where Ryan was

unaware.

The next day, March 5, 1949, Ryan arrived to the area,

insisting that they discuss the problem of what happened to

the gold. However, Noss demanded to see the money

before revealing the new hiding place. Ryan hinted

that if Noss did not reveal the whereabouts of the gold, Doc

would not live to enjoy it. An intense argument ensued and

Noss headed toward his car. Ryan, fearing Doc was

getting a gun, fired a warning shot in Doc’s direction,

demanding that Noss back away from the vehicle. Noss

refused to obey and Ryan fired again, hitting Noss in the

head, killing him instantly. Just twelve years after

discovering the treasure, Doc Noss died with just

$2.16 in his pocket. Ryan was charged with murder, but was

later acquitted.

As the years passed

Babe Noss held onto her claim at Victorio Peak, occasionally

hiring men to help her clear the shaft. However, it was a

slow process and in 1955, the White Sands Missile Range

unexpectedly

expanded their operations to encompass the

Hembrillo Basin. Babe began a regular correspondence

with the military requesting permission to work her claim,

but she was always denied. From that moment onward,

every attempt of Babe’s to clear the rubble from the plugged

shaft met with a military escort out of the area.

This was the beginning

of long legal battles over the ownership of the claim.

The military claim stemmed from a statement made by New

Mexico officials on November 14, 1951 which withdrew

prospecting, entry, location and purchase under the mining

laws, reserving the land for military use only.

However, disputing the military claim, New Mexico officials

stated that they leased only the surface of the land to the

military. Further, they stated that underground

wealth, in whatever form it took, belonged to the state or

to any legal license holders.

Becoming even more

complicated, a search of mining records failed to turn up

any existing claims including that of Doc

Noss. Additionally, the actual land where Victorio Peak is

located was not owned by the State of New Mexico, but

rather, by a man named Roy Henderson who had leased it to

the Army.

The

dispute was finally worked out when a federal court issued a

compromise of sorts, which stated the Army would continue to

use the surface of the land, but no one would be allowed on

the property without the Army’s consent. In effect, no one

could mine the treasure, and that included the Army and Babe

Noss.

Even though the military refused any of Babe’s efforts to

work her claim, it apparently did not refuse other military

personnel from exploring portions of Victorio Peak.

Two airmen from nearby Holloman Air Force Base would later

say that they had found the gold cavern from another natural

opening in the side of the peak. The soldiers, Airman

First Class Thomas Berlett and Captain Leonard V. Fiege,

said they had found approximately one hundred gold bars

weighing between forty and eighty pounds each in a small

cavern. After the discovery, Fiege told several people

that he had caved in the roof and walls to make it look as

if the tunnel ended.

Neither man being familiar with laws governing the discovery

of treasure on a military base, Fiege went to the Judge

Advocate’s Office at Holloman Air Force Base to confer with

Colonel Sigmund I. Gasiewicz. Now there were two

military commands involved.

Berlett and Fiege formed a corporation to protect what they

had found, as well as making a formal application to enter

White Sands for a search and retrieval of the gold. However,

White Sands issued an edict expressly forbidding them to

return to the base. In the summer of 1961, upon the advice

of the Director of the Mint, Major General John Shinkle of

White Sands allowed Captain Fiege, Captain Orby Swanner,

Major Kelly and Colonel Gorman to work the claim. On August

5, Fiege and his party returned to Victorio Peak,

accompanied by the commander of the Missile Range, a secret

service agent, and fourteen military police. Try as he

would, Captain Fiege was unable to penetrate the opening he

had used just three years earlier. General Shinkle finally

had enough and ordered everyone out. Later, Fiege would take

a lie detector test, which would allow Fiege back on the

missile range. This time, the military began a full-scale

mining operation at the Peak.

Fueled by suspicions that the military was working her

claim, Babe Noss hired four men to surreptitiously enter the

range. Though caught trespassing and escorted from the

area, the men reported that they had observed several men in

Army fatigues upon the peak. An affidavit dated

October 28, 1961, was signed to this effect, also claiming

to have seen a military jeep and a weapons carrier on the

mountain. Immediately reporting the activity to Babe

Noss, Babe contacted Oscar Jordan with the New Mexico State

Land Office, who in turn, contacted the Judge Advocate’s

Office at White Sands. In December 1961, General

Shinkle shut down the operation and excluded anyone from

entering the base who was not directly engaged in the

missile research activities.

In 1963, the Gaddis

Mining Company of Denver, Colorado, under a contract with

the Denver Mint and the Museum of New Mexico, obtained

permission to work the site. For three months

beginning on June 20, 1963, the group used a variety of

techniques to search the area; however, they failed to turn

up anything. Left is an aerial view of Victorio Peak looking

north. The roads are the result of the search.

In 1972, F. Lee

Bailey, became involved in the dispute, representing some

fifty clients including Babe Noss, the Fiege group, Violet

Noss Yancy, Expeditions Unlimited (a Florida based treasure

hunting group), and many others. Reaching a compromise

the military based allowed Expeditions Unlimited,

representing all of the claimants to excavate the peak in

1977. However, the Army placed a two-week time limit

on the group and they had hardly started before they were

forced to leave, without finding anything. The Army

then shut down all operations stating that no additional

searches would be allowed.

In 1979, Babe died

without ever finding the treasure. However, Terry

Delonas, her grandson, continued the family tradition and

formed the Ova Noss Family Partnership. By this time,

Babe’s story had spread across the nation, profiled in

several magazines and newspapers. Hearing about the

story, a man by the name of Captain Swanner, who was

stationed at White Sands Missile Range in the early 1960’s

came forward. Speaking to a Noss family member, he stated

that he had been the Chief of Security in 1961 and was sent

to inspect the report made by Airman Berlett and Captain

Fierge. After determining the accuracy of the two

men’s reports, the entire area was placed off-limits until

an official investigation could be conducted. Reportedly the

military was able to penetrate one of the caves and

inventory the contents. The gold was supposedly

removed from the cave and sent to Fort Knox. Though

the military confirmed that Swanner had served at White

Sands during this time, they claimed there were no documents

to support an investigation into the mine nor the removal of

the gold bars.

Today, Army’s official position on the whereabouts of the

gold is remains cautious, maintaining that the burden of

proof rests with the accusers. Many members of the Noss

family and friends believe that the military exploited

Babe’s claim and that the treasure is now gone. However,

Terry Delongas stated, "We're not accusing the military of

stealing the gold, but I do feel that the Department of the

Army in the 1960’s treated my grandmother unfairly.....

However, we’ve worked very hard over the years to establish

a working relationship with the military, and we're

certainly not going to jeopardize that by accusing them of

theft." The whole truth will probably never be known, but

there is no doubt that a treasure existed. Too much

evidence supports the treasure including photographs,

affidavits and relics still held by the Noss family.

In

a special act of Congress passed in 1989, the Hembrillo

Basin was “unlocked” for Terry Delonas and the Noss heirs;

however nothing has been found.

Epilogue

On January 10, 2010 Author Barbara

Marriott emailed me that she is writing a book on New

Mexico that will include a chapter about the Noss's and

Victorio Peak. She has written several books that look

very interesting.

www.barbaramarriott.com

October

11, 2012 Becca Gross (of

Prometheus Entertainment) emailed me that she's

currently working on a documentary series for the

History Channel, and wanted to check in

regarding the

possibility of an on-camera interview. In the second

season of "America's Book of Secrets," they reveal

lesser-known information behind some of America's most

mysterious organizations. In the episode she's currently

researching, they're looking at some of America's lost

treasures, including Victorio Peak. She thought my

knowledge might be a great contribution.

I told her that everything I know was gleaned from others,

so don't know what more to add, other than what

impressed me about the entire story. The ancient legend

is fascinating, along with the

disappearance of the treasure from the mountain while

being controlled by the government military base.

It's a never ending story of what

happens to the mentality of those possessed by greed

and fear.

I'll be looking forward to watching

this new documentary on "America's

Book of Secrets" when, and if it's completed.